After entering the new century, particularly following the financial crisis that emerged in Western societies in 2008, Chinese artists began leveraging economic means to actively participate in artistic activities within the Euro-American art system. On the other hand, the vibrancy of the art market also brought Western artworks directly into mainland China. These changes, objectively speaking, facilitated deeper mutual understanding and unintentionally dissolved certain "barriers" caused by geographical distance between East and West. Consequently, the psychological perception of the Euro-American contemporary art scene as the "center of the world" was partially eroded as familiarity grew.

China's art market has indeed developed rapidly since the turn of the century. As of now, it has taken a mature shape, consistently ranking among the global top three markets alongside the United States and the United Kingdom. As a result, the market has emerged as a force of significant influence on art, standing alongside traditional institutions like official art associations, academies, and art schools.

Against this backdrop, a multitude of art districts sprang up rapidly. In Beijing, iconic art zones such as 798 emerged, alongside others like Songzhuang, Caochangdi, Heiqiao, and No. 1 Ground. Similarly, other cities witnessed the rise of prominent art spaces, such as M50 in Shanghai, Chuangku in Kunming, the Blue Roof Art Center in Chengdu, and the Tank Loft in Chongqing. Additionally, a wave of private museums and commercial galleries came into existence, and some overseas art institutions, like the Ullens Center for Contemporary Art, entered China driven by market opportunities.

The establishment of these institutions significantly contributed to the formation of a new artistic ecosystem, providing a foundation for the survival and professional development of art industry practitioners, such as curators. The frequent emergence of “sky-high prices” in the market also drew considerable attention to contemporary art. With transaction volumes in the hundreds of billions, it has become increasingly evident that the widespread dissemination of contemporary art in China is becoming a more hopeful reality. After all, in a market economy, price represents a form of respect and recognition.

However, globalization and marketization have also brought entirely new challenges to the realm of contemporary Chinese art. For instance, some artists, particularly younger ones, have neglected the importance of local context as they gradually integrate into the global art scene. This has also led to a trend of "fragmentation" in art creation since the turn of the century. In 2010, art historian Lü Peng pointed out the inevitability of the arrival of the "fragmented" era in his essay The Fragmented Revolution. Indeed, after entering the new century, it has become increasingly difficult to identify cohesive, systematic artistic movements or collective phenomena.

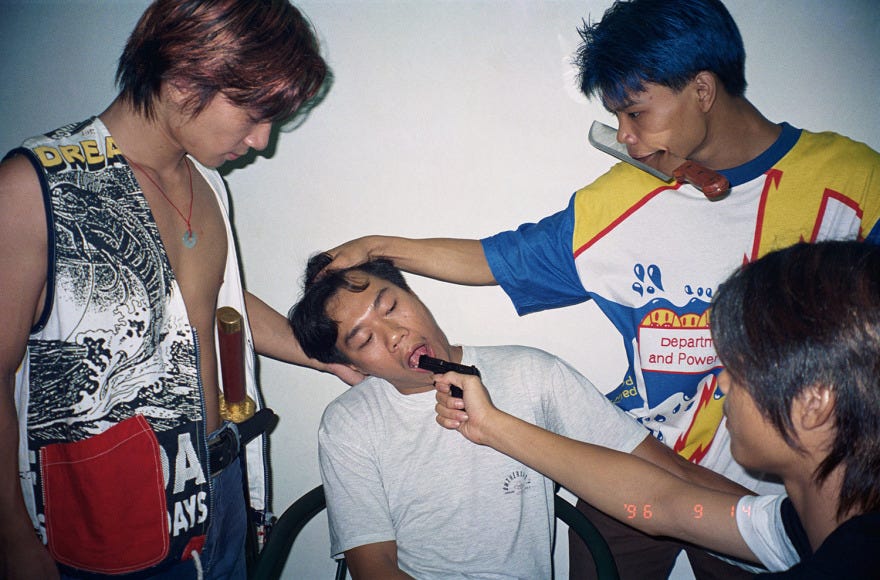

Although at the beginning of the century, some curators and institutions introduced art groups closely tied to consumer culture—such as Cruel Youth or The Cartoon Generation—these so-called new collectives have failed to achieve the same symbolic resonance as movements like the "85 New Wave," "Political Pop," or "Cynical Realism" of the 1980s and 1990s. These earlier movements served as defining artistic symbols of their eras, whereas their successors seem to lack the same cultural and historical weight.

In the field of painting, the growing influence of internet culture and high technology on everyday life has led many artists to move beyond "painting" as their sole medium of artistic expression. Increasingly, "integrated" elements have been incorporated into their creations. As such, the term "new painting" seems to more accurately capture the essence of the works emerging in the new century. Notably, "new painting" does not refer to a specific category or an art form with a defined ideological inclination. Instead, it signifies that painting has become one of many tools for artists to convey their ideas, rather than an end in itself.

In 2002, curator Zhu Qi organized an exhibition titled Cruel Youth at the Yanhuang Art Museum in Beijing, featuring artists such as Xie Nanxing, Yin Zhaoyang, Tian Rong, Xin Haizhou, He Sen, and Zhao Nengzhi. The curator sought to amplify the "self-reflective" and melancholic emotions evident in these young painters' works, revealing the dissolution of their external consciousness. In April 2004, an exhibition curated by Shu Yang, Chinese Video Painting, was held at the Beijing Seasons Gallery. This exhibition explored the fusion of painting techniques with video aesthetics, clearly articulating the concept of "video painting."

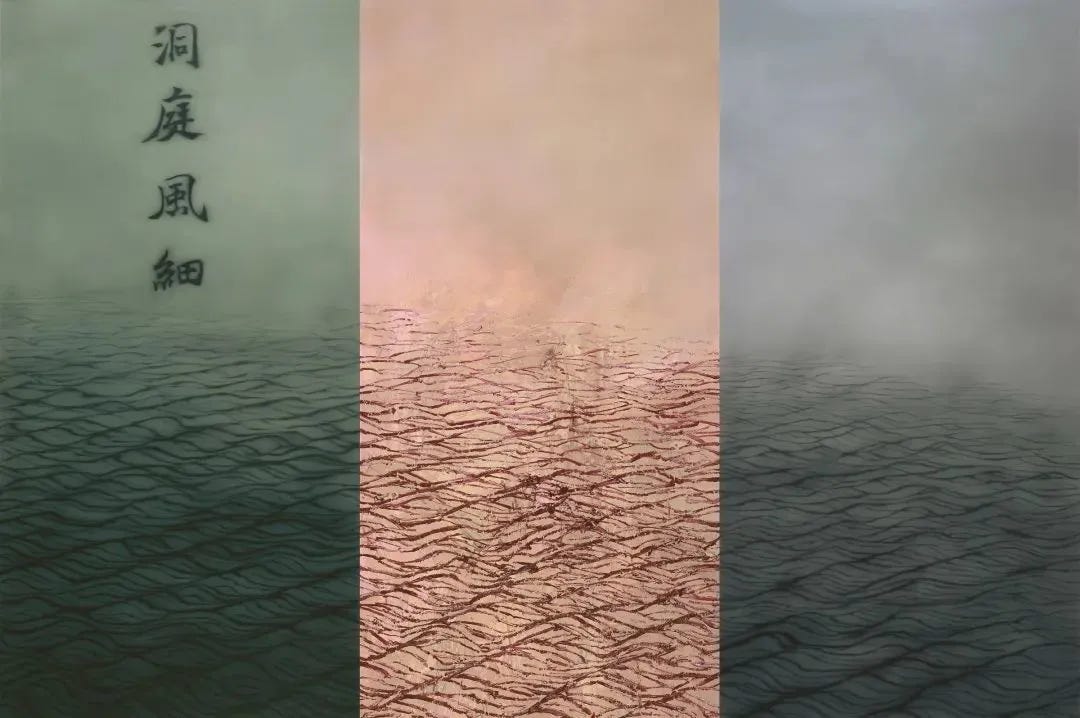

Meanwhile, artists who had already developed distinctive painting styles in the 1980s and 1990s began to embrace their own versions of "new painting." After leaving the Big Family series, Zhang Xiaogang incorporated more quotidian elements into his paintings. Fang Lijun’s works in the new century became more elaborate and vibrant, likely reflecting the artist’s increasing focus on the traces of life itself. Similarly, Yue Minjun, Zeng Fanzhi, and Zhou Chunya began integrating more traditional Chinese painting elements into their "new paintings."

It is undeniable that painting has become more "individualistic" in the new century. While trends may hold their allure, most artists seem more inclined to express their personal concerns and the issues they deem most significant, rather than merely following the currents of the art world.

Around 2010, with the commencement of the Xishan Qingyuan (Tranquility Beyond Streams and Mountains) series of exhibitions in the UK, US, Spain, Japan, and Chengdu, China, a new phenomenon in painting emerged. Some contemporary artists began dedicating their efforts to exploring themes rooted in Chinese culture. Indeed, during the 1980s, tradition was often the primary target of critique for avant-garde art. However, as Chinese intellectuals gained a deeper understanding of Western civilization and engaged in closer interactions with it, they began reexamining their attitudes toward their own cultural heritage. Former performance artist Dai Guangyu, for instance, has increasingly drawn on traditional art forms and cultural resources in his recent works.

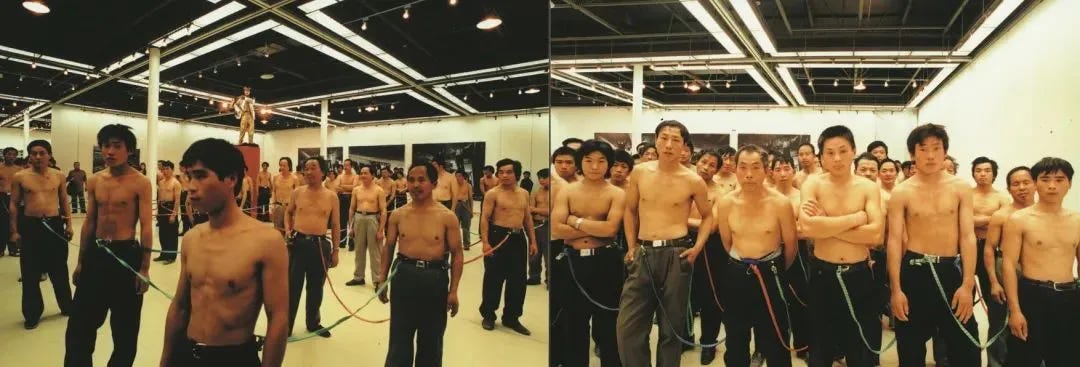

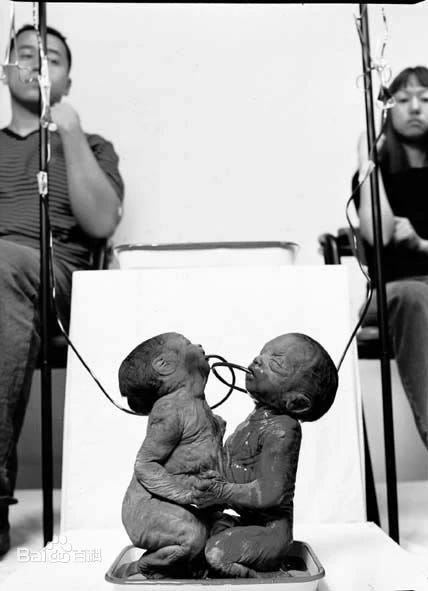

Performance art also flourished in the new century, becoming increasingly dynamic. In April 2000, Obsession with Harm, curated by Li Xianting, was held at the sculpture studio of the Central Academy of Fine Arts. The exhibition sparked significant discussion, with its central controversy revolving around the ethical challenges posed when human or animal corpses are directly used in artworks. Many of the exhibited works evoked physical discomfort among viewers. Similarly, curator Gu Zhenqing organized the nationwide Man and Animal series of performance art exhibitions, which were held consecutively in cities such as Beijing, Chengdu, Nanjing, Guilin, Changchun, and Guiyang. These exhibitions delved into the relationship between humans and animals.

Regardless of whether the artists' intentions were to provoke public attention or to advance the development of art itself, performance art in the early years of the new century drew considerable attention. Other notable projects continued to emerge. The Gao Brothers organized and presented the Utopia of Embrace for Twenty Minutes series in cities like Jinan (2000). Liu Chengrui (Guazi) created A Round Red Sun, in which the artist confined himself with a massive stone in a custom-built space, using a silver hook embedded in his collarbone to bind himself, laboring daily to chip the stone into fragments. Addressing environmental concerns, the Nut Brothers launched The Dust Plan (2015), spending 100 days vacuuming smog from the streets of Beijing and using the collected dust to craft a single brick.

These diverse and often provocative works illustrate the multifaceted evolution of performance art in contemporary China, as it grappled with ethical, cultural, and environmental themes while capturing the public's imagination.

We can also observe that as participants in performance art have grown younger, their works have increasingly incorporated elements closely tied to daily life, infusing them with a sense of lived reality. In our fast-changing era, the immediacy and fluidity of performance art ensure that it remains closely aligned with the spirit of the times. At the dawn of the new century, while conceptual art had already been present in China for some time, it often suffered from a lack of foundational theoretical frameworks and relied heavily on ambiguous interpretations. This led to conceptual art often being perceived as overly abstract and detached in its logic. Many artists' self-proclaimed "profound" ideas frequently eluded public understanding. Nevertheless, its popularity provided artists uninterested in brushwork, sensuality, or visual experience with a platform to assert the importance of their intellectual pursuits.

Post-2000, with technological innovation, more conceptual artists began experimenting with video art as a medium. Notable examples include Wang Gongxin's My Sun (2000), Wang Jianwei's Theatre (2002), Wang Guofeng's Oblique Island Project (2000) and I Love Beijing Tiananmen (2001), Cui Xiuwen's Three Realms (2004), and Gu Dexin's A4 (2001–2003).

Zhang Peili, after 2000, continued utilizing archival films imbued with political and historical memory to create new works. Cui Xiuwen's Ladies’ Room (2000), shot in the "Heaven on Earth" nightclub, became one of her most renowned pieces, addressing the realities of contemporary Chinese society much like Yang Fudong's The First Intellectual (2000). In 2017, Xu Bing's documentary Dragonfly Eyes, created using omnipresent surveillance footage, poignantly depicted the precarious realities that every individual in contemporary China might face.

Qiu Zhijie, as a pioneering advocate of avant-garde art, has made significant contributions not only to performance and video art but also to promoting integrated art practices. On May 2, 2009, Gu Dexin completed his final artwork, 2009-5-2, at the Continua Gallery in Beijing's 798 Art District, marking his official retirement from the art world. Meanwhile, Huang Yongping's Bat Project III was withdrawn from the Guangzhou Triennial, once again underscoring how political complexities continue to exert influence within the art world.

These developments reflect how art in China, as it navigates the new century, has not only expanded its mediums and techniques but also become a vital arena for grappling with cultural, social, and political issues.

Living in the small city of Yangjiang in Guangdong, Zheng Guogu began, after 2000, to transform his earlier focus on "Yangjiang youth" through video technology into immersive, site-specific integrated art by appropriating sculptures and ready-made objects. Similarly, a new generation of younger artists has been employing conceptual and multidisciplinary approaches to present their works in increasingly innovative ways. For instance, Liu Ding has directed his attention to the cultural transformations brought about by consumerist society. His creations often revolve around themes deeply embedded in consumer culture, such as buying and selling, renovations, furniture, and branding—concepts that are inherently tied to the lived realities of modern life.

In 2016, artist Hu Yinping adopted the fictional persona of a buyer named "Xiao Fang" to engage her mother in discussions about starting a hat-weaving business. Over the following 12 months, she witnessed how the business significantly transformed her mother's personality and confidence. For many of China's underprivileged citizens, the lack of avenues to generate economic value leads to severe physical and material deprivation, which in turn fosters a deep sense of spiritual inferiority. Through what she described as an act of "deception," Hu sought to disrupt and transform this cycle, using her art as a means of intervention to bring about change.

This intersection of art, life, and social consciousness exemplifies the ways in which contemporary Chinese artists are pushing boundaries, addressing societal issues, and reshaping the relationship between art and everyday existence.

Over the past eighteen years of the new century, what has been labeled as conceptual art, video art, installation, or integrated art has proven difficult to classify. The age, gender, and educational backgrounds of the artists behind these works defy broad categorization. What can be confirmed, however, is that these forms of art maintain a close relationship with reality—whether on a spiritual level, through actions, or in connection to historical contexts. Meanwhile, sculpture, as another art form, underwent a fundamental shift after 2000. Moving away from its previously personal or utilitarian nature, it began gravitating toward public spaces and conceptual approaches, increasingly exerting influence within public life and events. A review of new-century sculpture also reveals the enduring presence of many familiar names who had already been active since the 1980s and 1990s: Sui Jianguo, Chen Wenling, Zhan Wang, Xiang Jing, Lin Tianmiao, Cao Hui, Zhang Dali, Jiao Xingtao, Shi Jinsong, and others.

The onset of the U.S.-China trade war on July 6, 2018, followed by the outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020, marked a turning point in decades of globalization, especially the model of global advancement driven solely by economic logic. As a country deeply entangled in the mechanisms of globalization, the trade war significantly impacted both the Chinese government and the general public. Even within the realm of art, artists and critics could not escape the ripple effects of these economic disruptions. Indeed, in many respects, economics has proven to be a more potent and practical force than politics in shaping societal and industrial developments. Economics has also become a pivotal force reshaping the landscape of contemporary Chinese art in the new century.

Thus, as Chinese contemporary art enters its fourth decade, it faces a more complex and challenging situation than ever before. The interplay of economic forces, global transformations, and domestic pressures has created an environment where the evolution of art is deeply intertwined with broader societal currents. This complexity underscores the resilience and adaptability required for the continued growth of Chinese contemporary art in an increasingly unpredictable world.

This challenging situation stems not only from external ecological conditions but also from a lack of vitality and creative drive within the artistic community itself. Although the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum in New York hosted the exhibition Art and China After 1989: Theater of the World on January 6, 2018, the featured works that truly resonated and held influence were predominantly created during the 1980s, 1990s, and the early 2000s. Notably, the younger generation of artists has not successfully taken the "creative baton" from their predecessors. This stagnation may be attributed to individual talent gaps or broader historical and societal contexts that shaped the environment in which they create.

Furthermore, a series of ethical controversies has eroded the perceied "moral advantage" that contemporary artists once seemed to enjoy, leading to a crisis of trust. For instance, in the 1993 Venice Biennale artwork loss incident, Hong Kong art dealer Johnson Chang—once praised for helping mainland artists gain international recognition—was labeled a "heartless" businessman by some media outlets and artists. However, these accusations often overlooked the historical context and circumstances of the time, revealing significant discrepancies in how history is interpreted and judged.

Thus, even as Chinese contemporary art marks its 40th anniversary this year and remains as bustling as ever, it faces profound and persistent challenges. As societal contexts and market dynamics continue to shift, the road ahead for contemporary art is as uncertain as it was four decades ago—a vast, blank canvas waiting to be filled. Yet, this very blankness offers immense opportunities and space for those bold enough to innovate. After all, art history has always been shaped by an endless array of miracles waiting to unfold.

Thanks for including so many images! 🙏